King Kong (1933)

King Kong (1933)

Film music was forever changed by Max Steiner’s 1933 score for King Kong. For the first time a sound film was accompanied by an original non-diegetic score that paralleled, supported and enhanced the narrative, pioneering the techniques and principles that have governed film scoring ever since. Legendary for its developments in stop-motion animation and special effects, the film inspired Peter Jackson to become a director,[1] remaking it for a modern audience in 2005. By examining the respective contexts that led to their composition, and illustrating the musical approaches and objectives of their composers, we will see how both scores respond to the necessary requirements of the films and the different interpretations of the same story.

Both versions of King Kong are products of their ages. The former came from the early Golden Age, when sound film was in its infancy – filmmakers wrestled with the basics of form and narrative and did not know how to deal with music, so movies would have one or two diegetic cues between the titles and nothing more.[2] The latter was from the blockbuster age of huge-budget cinematic experiences with mind-blowing special effects and technology merging fantasy and reality. Three hours long (compared 1933’s 96 minutes), it followed a tradition of modern-day epics lead by Jackson’s own Lord of the Rings trilogy, while motion-capture and CGI recreated the terror felt by 1930s audiences for cinema-goers of the 2000s with a believable and realistically-animated Kong.

King Kong (2005)

King Kong (2005)

Both scores emerged from troubled circumstances. James Newton Howard was hired after Howard Shore left the project, with five weeks to write three hours of music (compared to Steiner’s 75 minutes in eight weeks). He composed for 18 hours a day with orchestrators and copyists working overnight, recording the next day and video-conferencing with Jackson to review each cue less than 24 hours after it had been conceived.[3]

Steiner’s film was plagued by budget issues, but the animations had the filmmakers concerned:

[The producers] thought that the gorilla looked unreal and that the animation was rather primitive. They told me that they were worried about it, but that they had spent so much money making the film there was nothing left over for the music score…[4]

Ultimately producer Merian Cooper personally funded the entire score,[5] resulting in the first non-diegetic film score that utilised the methods of opera, music theatre and the silent movies to develop a musical illustration of the narrative that expressed all that the visuals could not. King Kong was hugely successful[6] and Steiner’s pioneering score demonstrated the potential of original music:

The music of Kong … demonstrates, for the first time in the ‘talkies’, that music has the power to add a dimension of reality to a basically unrealistic situation…[7]

Both composers took advantage of contemporary technology in utilising relatively large forces. Following a trend for larger and louder, Howard combined a symphony orchestra of over 100 musicians, a choir, ethnic solo instruments and electronics, with the aid of eight orchestrators and four conductors.[8] Musical complexity was balanced by the flexibility of digital recording, allowing for instant reviewing of cues and the adjustment of balances through careful mixing, while visual cueing enabled perfect synchronicity in single takes.

Max Steiner conducting King Kong (1933)

Max Steiner conducting King Kong (1933)

In 1933 the standard setup was a three-hour recording session with a 10-piece orchestra and one microphone,[9] but Steiner scored for 46 musicians with lots of doubling – six woodwinds played up to four instruments per cue, violins doubled on viola and one violist also covered the celeste.[10] Orchestral imbalance meant brass and percussion overpowered the strings, but, without modern mixing techniques, Steiner compensated through orchestration – reinforcing the basses with tubas, using saxophones to avoid weak woodwind registers – and conducted without synchronisation aids by editing multiple takes together.[11]

The musical language of both composers was relatively modernist, but never as modernist as concert music of the time. Steiner’s musical language was no more advanced than late Richard Strauss, although Brown believes it would have been sufficiently shocking:

Steiner’s King Kong music … would no doubt have scandalized most concert-going audiences of the time with its open-interval harmonies and dissonant chords, its tritone motifs, or such devices as the chromatic scale in parallel, minor seconds…[12]

King Kong incorporates the use of early mickey-mousing – characteristic of Steiner’s style and Golden Age scoring – notably with the Chieftain’s synchronised footsteps, Kong searching for Jack on the cliff (especially the ‘sobbing’ when he stabs him) and the low strings imitating the aeroplanes.

Mickey-mousing was obsolete by 2005, and Howard’s concerned his score with defining the mood, for instance when Jack and Ann escape as we switch back and forth between frantic drumming as they run and tentative suspense as Carl prepares his trap. Horrifying aleatoric passages, fierce action music with relentless motifs, big emotional melodies, painful dissonances and sparse loneliness – these were all practices of the time. In tribute to the 1933 film (in addition to the use of Steiner’s cues in the theatre scene), Howard’s score contained a few ‘Steiner-isms’ – notably the 1930s-style musical flourish during the filming on the ship and his choice of leitmotif for Kong.

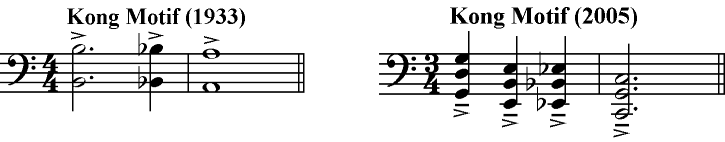

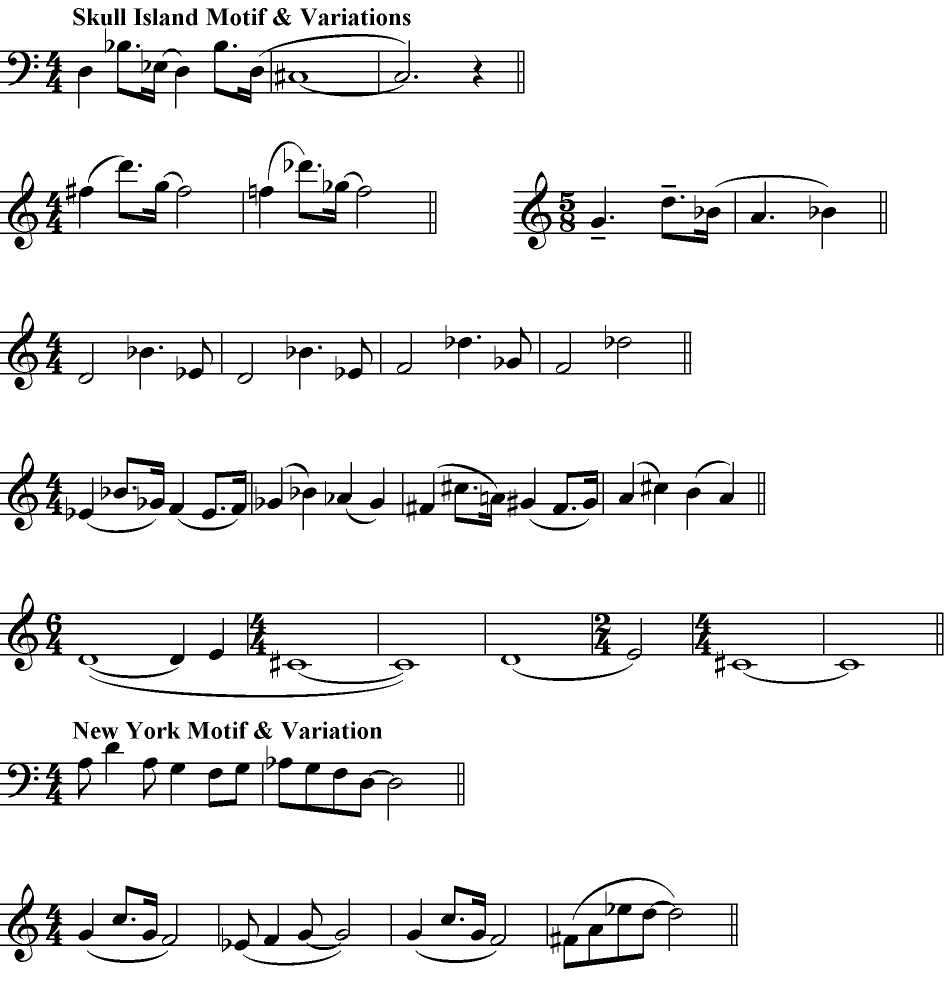

Both composers represented Kong with brief, fear-inducing motifs that could be developed and integrated into different contexts. Howard’s pays tribute to Steiner’s as they descend ominously:

Brutal and terrifying, both motifs play on audience expectations – in 1933 the film’s selling point was the idea of a giant gorilla wrecking havoc in New York City,[13] and audiences in 2005 came anticipating horror and destruction. Heard at the opening, portentous and frightening, in the brass and strings, the audience is primed for Kong’s terrifying first appearance.

In the 1933 version neither Kong nor Ann develop during the film – he remains the destructive, relentless monster, she the helpless damsel – and similarly the music does not evolve. The Kong motif is the most frequently used idea – played it against other motifs at key moments – but Steiner repeats it without significant variation. The Ann motif, more lyrical and feminine but with opening notes derived from Kong’s brazen masculine motif, also does not develop – instead, as Franklin argues, it heightens the tension through intensification by brutal repetition.[14] The motifs evolve to form the love theme, but this is used ambiguously[15] and sparingly.

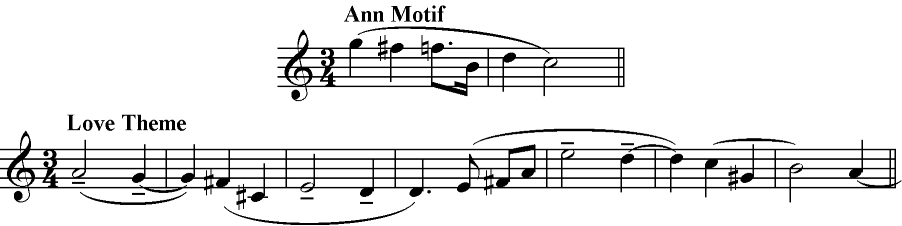

Howard’s Kong motif appears during early encounters with Kong, but he develops it for later use:

Kong and Ann are more detailed in the 2005 version thanks to the sophisticated animation and a more complex Ann. Howard’s brutal and primitive Kong motif is gradually replaced as his character develops by themes highlighting the unveiled aspects of his personality:

Concerned less with character-based motifs (there is no single general-purpose motif for Ann), Howard’s score concentrates on the contrasting worlds of Skull Island and New York instead:

The Skull Island motif, heard in the opening cue, is the most frequently used idea. Low and mysterious in the horns and strings, it signifies the island’s mythology; and once we reach the island it develops to signify many different emotions, climaxing in the high strings and woodwinds.

The New York motif is has a jaunty, jazzy style, signifying the 1930s culture for a 2000s audience in a way that was not necessary in 1933 (the earlier film being set contemporaneously). This motif is tied to Ann (for instance, when she entertains Kong on the island) as well as the modern world.

However the shape of the motif belies further meaning – both the contour and rhythm of the start of the New York motif are similar to that of Skull Island motif. Although Howard never integrates the ideas, the similar shape and feel creates a sense of cohesion between the two worlds in a more organic and interconnected way than had they been wildly different – the New York motif represents a Darwinian evolution from the quasi-prehistoric world of Skull Island to twentieth-century New York that mirrors Kong’s detailed portrayal and humanisation as an ancestor of man.

Kong and Ann - King Kong (1933)

Kong and Ann - King Kong (1933)

Steiner’s score famously uses no music until the boat is approaching the island, whereas Howard scores the (much longer) story before the island quite considerably. Steiner’s music appears to emerge from the fog, linking the non-diegetic with the fantastical world of Kong.[16] With audiences unaccustomed to music not justified visibly, Steiner blurs the distinction between the orchestra and the drumming – Jack confirms the drums as diegetic, drawing the audience’s attention away from the non-diegetic harp and strings. Howard uses similar techniques, with an ethereal and indistinct underscore as the ship enters the fog, and drums rising to the foreground as if they might be diegetic. Gorbman’s assessment of Steiner’s approach can also be applied to Howard’s cue:

The music initiates us into the fantasy world … It helps to hypnotize the spectator, bring down defenses that could be erected against this realm of monsters, tribesmen, jungles, violence.[17]

Both scores use primitive musical devices to portray the mythology of the island. Although Howard uses parallel fourths and fifths for Kong’s barbaric motif, he treats the natives with a sense of ethereal mystery, scoring their initial encounter as a suspense-based survival-horror cue. Furthermore, he accompanies the sacrificial ritual with only percussion and drums, corresponding to their portrayal as a voodoo-based culture, whereas Steiner’s Sacrificial Dance stays firmly in the Western European tradition,[18] utilising primitive rhythms and parallel fourths and fifths for the natives and their dances (portrayed as a stereotypical African tribe) – crude by modern standards, but a common device in the Golden Age to portray less-civilised cultures, as Brown notes:

What the filmmakers were going for in this sequence was affect, not realism. Where the use of genuine native music … would have added, for 1930s American audiences, a degree of consummatedness that would have cut into the affective response, the use of certain musical “mythemes,” such as open fourths and fifths and heavy motor rhythms, evokes an unconscious reaction of what Barthes would call “nativicity”.[19]

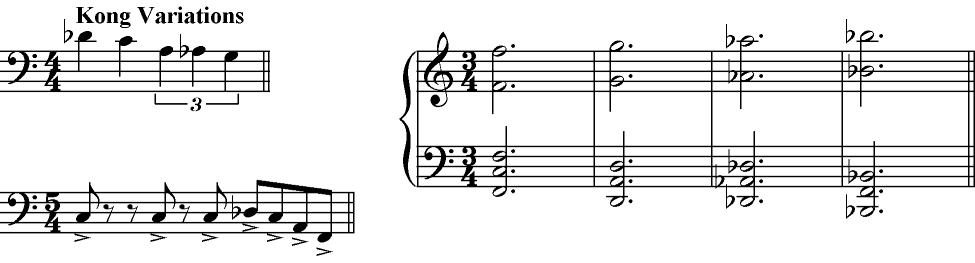

The most significant difference between the films is their portrayal of Kong and his relationship with Ann, most clearly in the relative sophistication of the animations. Steiner’s score elicits little sympathy for the title character – its main purpose being to scare and terrify – but Howard’s follows Jackson’s approach to humanise the monster and pity his loneliness and victimisation. Jackson’s Kong is able to express himself fully, and so the score treats him as any other character; whereas Steiner’s music told the audience what Kong was feeling, because the animations could not. With dissonant brass for his brutality contrasted with yearning melody for his tragedy and loneliness, Steiner aids the audience in viewing Kong as a character rather than an effect, as Palmer describes:

[T]he music is required … to explain to the audience what is actually happening on the screen, since the camera is unable to articulate Kong’s instinctive feelings…[20]

This is most apparent in the finale. From the moment that Kong escapes, Steiner continually intensifies the Kong motif – an unrelenting sense of terror with an emphasis on his rampant destruction. Similar to Ann’s first kidnapping, Steiner intensifies the motif as he steals a woman he mistakes to be Ann, the music engendering the same feelings of terror as in the earlier scene.

By this point in Jackson’s film a sympathetic link between Ann and Kong has already been established. While Kong is imprisoned in the theatre there is a stark juxtaposition between excerpts of Steiner’s furious score and his expression of tiredness and sadness, uncomfortably at odds with Steiner’s brutal Sacrificial Dance in this context. During his destructive escape the music takes a more neutral tone than Steiner’s (there is no angry Kong motif, instead generic action music heightens the tension while refusing to take sides) before finally settling with lyrical and emotional melody once he is reunited with Ann.

Kong and Ann - King Kong (2005)

Kong and Ann - King Kong (2005)

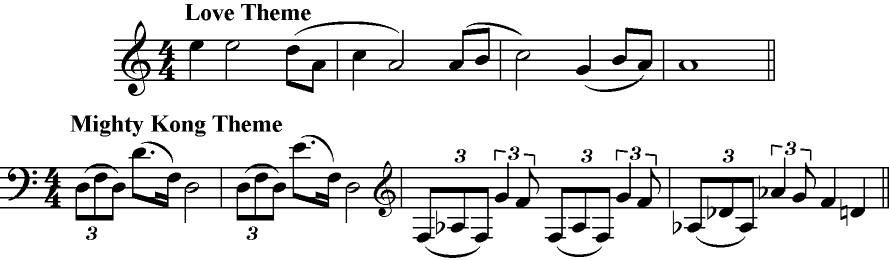

The differences in their reunions are striking. In 1933 Ann is kidnapped – screaming with more motif intensification – and the music ascends as he climbs, always horrific and frightening. In 2005 Ann finds Kong, and time stops as she steps into focus – a soft musical seduction as she comes closer. Danger and fear are vanquished and, as he picks her up, the oboe begins their love theme, heard previously on the island. This could have come straight from a romantic film (the gentle oboe, delicate piano, appassionato strings) but certainly not from 1933’s horror film. The skating scene – with its exciting harp and piano broken chords, soaring strings and noble horns – is the climax of the romantic story at the heart of this film. What follows is not a triumph over evil but the tragedy of star-crossed lovers from incompatible worlds.

Steiner’s music maintains the feeling of intensified terror, portraying an endless stream of chaos. We assume that, as Kong reaches the top of the Empire State Building, this will be the end for Ann – the tension and fear invoked by the relentless repetition of his motif points towards a tragic finale. With Howard’s Kong there is a sense of urgent desperation as he flees the army in panic – the music is distressed, not excited, as he runs – and, as with Steiner, the music increases in pitch and tension as he climbs. At the summit the score relaxes with a momentary sense of glory; but a sombre and tired acceptance of inevitability accompanies the approach of the fighters. Steiner’s Kong fights the planes in musical silence – the sound effects dominating the soundscape – but Howard’s watches their approach to the sound of a drum beating out an execution. The music turns solemn, broad and heavy – the sound of imminent defeat, not victory.

As Kong dies Steiner uses a brief but passionate burst of the love theme to bring relief from the chaos, but Howard scores his death as a tragedy – that of an antihero, not an antagonist – as a solo treble humanises his last moments, accompanied by soft harp and strings. The elegy that follows reprises an ambiguity heard when Kong is first captured – overwhelming mournfulness corresponds to Kong’s defeat, but a ray of hope breaks through the tonality producing a similar sense of relief to the end of Steiner’s score, both composers leaving the audience with a feeling of peaceful resolution – although whether it is New York’s peace or Kong’s depends entirely on the interpretation.

Kong imprisoned - King Kong (1933)

Kong imprisoned - King Kong (1933)

Max Steiner’s and James Newton Howard’s King Kong scores are products of their time – the first utilised the techniques of music theatre and late Romantic opera to extend the previously negligible role of music within film; the latter followed a tradition of epic blockbusters to maximise emotional response and increase the power of the narrative. Both composers wrote symphonic, leitmotif-based scores to fulfil the requirements of their movies – their interpretations diverging as the stories progressed, dictated by the nature of their films. Steiner produced the fear factor to convince the audience despite the rudimentary animations, while the emotional depth and variation of Howard’s score corresponded to the already-convincing multi-dimensional portrayal of his title character.

Steiner described King Kong as ‘a picture made for music – one which allowed you to do anything and everything’[21] and it heralded the beginning of Steiner’s fame and of film music itself. Howard expressed similar sentiments, inspired by the original: ‘I was a King Kong fanatic as a kid … I had a tremendous amount of feeling for the idea of this movie’[22] – his passion manifesting itself in the soaring melodies and tempestuous ostinati that pervade his score. Working 72 years apart, both composers created unique interpretations of the same story by utilising similar techniques, drawing upon their musical contexts, supporting the overarching filmic requirements, and allowing their respective audiences to experience the tale of how “it was Beauty killed the Beast”.

Reunion - King Kong (2005)

Reunion - King Kong (2005)

Notes

- P. Jackson, Interview with David Stratton, At the Movies (Accessed 6 February 2014), http://www.abc.net.au/atthemovies/txt/s1529210.htm

- K. Donnelly, ‘The Hidden Heritage of Film Music: History and Scholarship’, Film Music: Critical Approaches, ed. K. Donnelly (Edinburgh, 2001), 8

- C. Bacon & M. Nowak, ‘Post-Production Diary: The Music of Kong Part 1’, King Kong: 2 Disc Special Edition, dir. Peter Jackson 2005 (Universal, 2006), DVD, 824 245 6

- M. Steiner, ‘Max Steiner on Film Music’, Film Score: The View from the Podium, ed. T. Thomas (New York, 1979), 76

- Raksin remembers: ‘Cooper said the magic words, which I quote: “Maxie, go ahead and score the picture … and don’t worry about the cost, because I will pay for the orchestra.”’ D. Raksin, ‘David Raksin Remembers His Colleagues: Max Steiner’, American Composers Orchestra (Accessed 27 January 2014), http://www.americancomposers.org/raksin_steiner.htm

- After being over budget at almost $700,000 it took at least $1.7 million at the box office. ‘King Kong’, IMDb (Accessed 5 February 2014), http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0024216/

- C. Palmer, The Composer in Hollywood (New York, 1990), 28

- ‘King Kong’, Hollywood Studio Symphony (Accessed 2 February 2014), http://www.hollywoodstudiosymphony.com/cd2.asp?ID=188

- Raksin, op. cit.

- J. Morgan in M. Steiner, King Kong: The Complete Film Score, Moscow Symphony Orchestra, William Stromberg (Naxos), 1997/R2005, CD, 8.557700, sleeve notes, 5

- ibid., 6-7

- R. Brown, Overtones and Undertones: Reading Film Music (Berklee, 1994), 118

- Advertisements for the movie capitalised on the idea of ordinary New Yorkers fleeing in terror from Kong’s destruction. P. Franklin, ‘King Kong and Film on Music: Out of the Fog’, Film Music: Critical Approaches, ed. K. Donnelly (Edinburgh, 2001), 91

- ibid., 95-6

- Steiner uses the love theme to represent both Jack and Ann on the boat and Kong and Ann in his cave and in the finale.

- Stilwell and Buhler have identified a ‘fantastical gap’ between the diegetic and non-diegetic music during the island approach that blurs the placement and explanation of the music and thus creates a sense of fantasy. R. Stilwell, ‘The Fantastical Gap between Diegetic and Nondiegetic’, Beyond the Soundtrack: Representing Music in Cinema, ed. D. Goldmark, L. Kramer & R. Leppert (Berklee, 2007), 187-9

- C. Gorbman, Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music (Indiana, 1987), 79

- An approach that did not win over critics such as Molly Merrick: ‘musical effects in the picture become a bit comic, as for instance when we hear a full symphony orchestra in the heart of the dangerous Kong country when there should have been nothing but tom-toms’, although her complaints seem not to be restricted just to the native dances but the use of Western music throughout the film. Quoted in King Kong: The Complete Film Score, sleeve notes p4

- Brown, op. cit., 41

- Palmer, op. cit., 29

- Quoted in ibid., 27

- J. Newton Howard, ‘Post-Production Diary: The Music of Kong Part 1’, King Kong: 2 Disc Special Edition

Bibliography

- R. Brown, Overtones and Undertones: Reading Film Music (Berklee, 1994).

- J. Buhler, ‘Analytical and Interpretive Approaches to Film Music (II): Analysing Interactions of Music and Film’, Film Music: Critical Approaches, ed. K. Donnelly (Edinburgh, 2001), 39-61.

- M. Cooke, A History of Film Music (Cambridge, 2008).

- K. Donnelly, ‘The Hidden Heritage of Film Music: History and Scholarship’, Film Music: Critical Approaches, ed. K. Donnelly (Edinburgh, 2001), 1-15.

- C. Erb, Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood Icon in World Culture (Wayne, 2009).

- P. Franklin, ‘King Kong and Film on Music: Out of the Fog’, Film Music: Critical Approaches, ed. K. Donnelly (Edinburgh, 2001), 88-102.

- C. Gorbman, Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music (Indiana, 1987).

- P. Jackson, Interview with David Stratton, At the Movies (Accessed 6 February 2014), http://www.abc.net.au/atthemovies/txt/s1529210.htm

- K. Kalinak, Settling the Score: Music and the Classical Hollywood Film (Wisconsin, 1992).

- C. Palmer, The Composer in Hollywood (New York, 1990).

- D. Raksin, ‘David Raksin Remembers His Colleagues: Max Steiner’, American Composers Orchestra (Accessed 27 January 2014), http://www.americancomposers.org/raksin_steiner.htm

- M. Slowik, ‘Diegetic Withdrawal and Other Worlds: Film Music Strategies before King Kong, 1927-1933’, Cinema Journal, 53/1 (2013), 1-25.

- R. Stilwell, ‘The Fantastical Gap between Diegetic and Nondiegetic’, Beyond the Soundtrack: Representing Music in Cinema, ed. D. Goldmark, L. Kramer & R. Leppert (Berklee, 2007), 184-202.

- ‘King Kong’, Hollywood Studio Symphony (Accessed 2 February 2014), http://www.hollywoodstudiosymphony.com/cd2.asp?ID=188

- ‘King Kong’, IMDb (Accessed 5 February 2014), http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0024216/

Discography

- J. Newton Howard, King Kong: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Hollywood Studio Symphony Orchestra, Pete Anthony/Mike Nowak/Bruce Babcock (Decca), 2005, CD, 476 5224.

- M. Steiner, King Kong: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, RKO Studio Orchestra, Max Steiner (Sony Classical), 1999/R2010, CD, 886976385927.

- M. Steiner, King Kong: The Complete Film Score, Moscow Symphony Orchestra, William Stromberg (Naxos), 1997/R2005, CD, 8.557700.

- King Kong: 2 Disc Special Edition, dir. Peter Jackson 2005 (Universal, 2006), DVD, 824 245 6.

- The Original King Kong, dir. Merian C. Cooper & Ernest B. Schoedsack 1933 (Universal, 2005), DVD, 8237617.